The city of Amsterdam is always growing. This was also the case in the nineteenth century. Trade, industry, work and living space: to connect all this, a good transport network was needed.

1901

The area where De Hallen is now located was once water: the Kwakerspoel. In the seventeenth century, during the enormous growth of Amsterdam, the lake was dug to provide space for sawmills for housing and shipbuilding. The area grew into a busy zone on the western edge of the city. Around the nineteenth century, the wood market collapsed due to foreign imports, and the mills fell into disuse. The city grew at the seams, the Kwakerspoel was filled in and the windmills demolished. The vacant land turned out to be ideal for something new: a parking space for the electric tram.

In the nineteenth century, horse and carriage was an important means of transport in Amsterdam. One of the first forms of public transport was therefore the horse-drawn tram, which entered the city in 1875. Starting with a line that only commuted between Dam Square and Leidsebosje, there were already fifteen lines in 1900. In that year, it was decided to electrify the tram network. To store and maintain the trams, they started designing a tram depot.

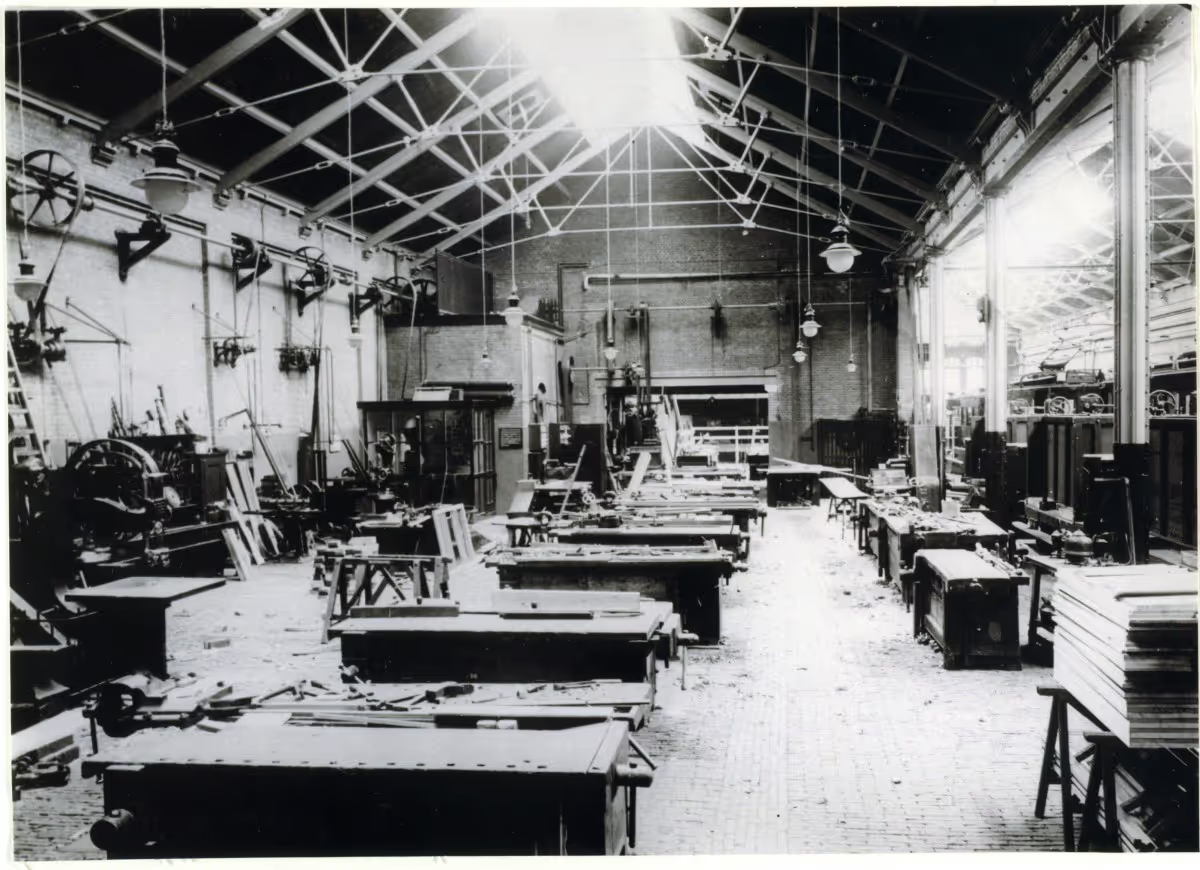

De Hallen zijn ontworpen door de Dienst der Publiek Werken. In opdracht van de gemeente Amsterdam hield deze dienst zich vanaf 1850 tot 1980 bezig met het ontwerpen van gebouwen met een openbare functie: bruggen, scholen, wegen, en dus ook tramremises. De architecten bleven vrijwel altijd anoniem. De tramremise bestaat uit zeven hallen en een externe timmer- en schilderwerkplaats (de huidige Hal 17) en is tussen 1901 en 1928 in fases gebouwd. Kenmerkend aan het gebouw is het veelvuldig gebruik van bakstenen en de prachtige spantconstructies die overal in het pand te vinden zijn. Mede hierdoor heeft de Hallen raakvlakken met de Amsterdamse School, een stijl in de bouwkunst die in het begin van de twintigste eeuw ontstond en zich onderscheidde door een expressieve bouwwijze. De huidige centrale passage loopt van de Tollensstraat naar de Ten Katemarkt. Deze grote, lichte ruimte was vroeger de traverseerhal. Hier kwamen de trams binnen om vervolgens met behulp van speciale rolwagens naar een van de dwarsliggende hallen geleid te worden voor stalling of reparatie.

The demand for new trams was enormous and, of course, they all had to be maintained. The tram depot quickly became the beating heart of the neighborhood.

1932

The city grew. There were more tram lines and more space was needed for the trams. To meet this requirement, depots were added, such as the tram depot in the Havenstraat in Amsterdam-Zuid and the Lekstraat depot in the Rivierenbuurt. The Tollensstraat depot was also expanded. Between 1908 and 1928, the complex kept getting a little bigger. For example, the spaces east of Tollensstraat (now known as the small passage) were completed and used as parking for tram side cars. Halls 2 and 3 were expanded towards Bellamy Square.

In 1932, the tram depot in the Havenstraat in Amsterdam-Zuid was made a lot larger. As a result, it was no longer necessary to park trams in Tollensstraat. From that moment on, the Tollensstraat depot was only used as a workshop.

During the war, tram traffic came to a standstill and many trams were transported to Germany. After the war, the trams returned: bigger, longer, more modern.

Deze nieuwe modellen vereisten veel onderhoud. In de jaren ’80 werkte Louis Dona in de Mechanische Onderdelen Werkplaats van de remise, als bankwerker. “Op een gemiddelde dag liepen er zo’n tweehonderd man rond. Bij ons op de afdeling zaten we met iets meer dan twintig. Elke keer als er een tram binnenkwam, werd die helemaal gestript — klapraampjes, monitoren, alles. De onderdelen gingen naar het magazijn, werden gereviseerd, en daarna zetten wij de tram weer helemaal in elkaar.” Op zijn afdeling stond ook een enorme hamer. “Die sloeg zo hard, dat bij de winkels op de Kinkerstraat de potjes uit de vitrines rammelden.” Louis werkte meer dan twintig jaar in de remise. Een van zijn mooiste herinneringen? Het bezoek van Herman Brood. “Die dag werd er niks gedaan. Iedereen kwam kijken. We hebben zó gelachen.” Toch hield het op. De trams werden steeds groter en pasten op den duur nauwelijks nog in het gebouw. Uitbreiden kon niet meer. De stad was om het complex heen gegroeid. Andere werkplaatsen namen het over.

With the commissioning of the more modern and larger workshop in Diemen, the GVB left the Tollensstraat tram depot.

1996

In 1996, the curtain finally fell on the Tollensstraat tram depot. The GVB took the new main workshop in Diemen-Zuid into use and — after almost a century — the building in Amsterdam-West was no longer needed as a workshop. Louis Dona experienced the closure up close. “We found it terrible. Everyone who sat here. When we heard the bell here in West, we went shopping. Then we walked into the Kinkerstraat and one went here, the other went there. You could go anywhere. There was absolutely nothing to do in Diemen. Anyway, we had to leave. The building just about fell apart. When it rained, we had to put down pallets, otherwise you could barely walk through all that water.”

After a few more years of serving as a shelter for museum trams, the Tollensstraat depot closed its doors in 2005.

At the beginning of 2010, life unexpectedly returned to the empty draw. A group of activists, young people and artists used the building out of distrust of the plans for redevelopment.

2010

On Sunday, January 31, 2010, the tram depot was cracked by a group of activists, young people and artists who had little faith in the plans for redevelopment. The building had been empty for over five years and it had been almost fourteen years since the GVB left. The squatters wanted to use the space for small-scale cultural and social projects. They built courtyards, opened the doors to the public with theater performances and events, and even built a swimming pool. After much bickering with politicians, it was agreed that they would leave the building as soon as construction was carried out on the basis of a plan with support in the neighborhood.

In the same year, the Tramdepot Development Company (TROM) was established.

After years of tug-of-war and failed plans, TROM comes into the picture. An initiative group consisting of architect André van Stigt, local residents, future users and other stakeholders and sympathizers.

2013

It was clear even before 1996 that the building needed a new function. Various renovation plans were presented but failed. Even the demolition was on the table. In 2010, the Tramremise Development Company (TROM) was founded to change that. Their goal: to give De Hallen a new, sustainable and high-quality interpretation as quickly as possible — appropriate to the neighborhood and with a metropolitan appearance. And all of this in a financially profitable way.

To achieve this, we spoke intensively with the neighborhood and looked at what the building allowed. The space determined what could happen: “function follows form”. De Hallen had to become the working heart of the neighborhood again, and a vibrant cultural center.

After years of tug-of-war and failed plans, TROM comes into the picture. An initiative group consisting of architect André van Stigt, local residents, future users and other stakeholders and sympathizers.

In het herinrichtingsplan heeft architect André van Stigt zich ingezet om sporen van de originele functie te behouden. Zo lopen er nog altijd tramrails door de centrale passage en op de muren verwijzen de originele stenen nummerbordjes naar de erachter gelegen hallen.

Door de hoge lange zadeldaken die voor een groot deel uit glas bestaan, valt veel daglicht naar binnen. Mede hierdoor hebben De Hallen een prettig en ruimtelijk gevoel, wat nauw aansluit bij de visie van de herinrichting: waar de werkplaatsen van De Hallen ooit gesloten ruimtes waren

waarachter arbeid werd verricht, is het complex nu een open ruimte die voor iedereen toegankelijk is.Eén van de initiatiefnemers van Stichting TROM, Eisse Kalk, heeft over de renovatie het boek Nieuw Leven in De Hallen geschreven.

In oktober 2014 ontvangt André van Stigt de IJ-prijs uit handen van voormalig burgemeester Eberhard van der Laan. Samen openen zij, vijf jaar na de presentatie van de eerste renovatieplannen, op 5 februari 2015, De Hallen officieel.

After years of tug-of-war and failed plans, TROM comes into the picture. An initiative group consisting of architect André van Stigt, local residents, future users and other stakeholders and sympathizers.

2014

The FilmHallen has nine halls and a unique Parisien hall with the original interior of Cinema Parisien (1924). In Leescafé Belcampo, you can walk straight to OBA De Hallen, which together is good for a cultural program. Opposite is Beeldend Spraken: gallery and art loan for contemporary art.

Today, De Hallen is also about craftsmanship. At Recycle, bicycle mechanics are trained, Denim City is about denim innovation and you learn the trade at the Jean School. Young Bloods trains young people to become hairdressers in one year.